Negotiations #

Negotiations can be seen as either zero-sum games or as non-zero-sum games. The strategy behind the different approaches can result from a cultural background or from the relationship between the two parties.

A zero-sum negotiation results in one party winning and the other one loosing. In a car-sale, a (more or less) one off event, the seller tries to get as much as possible from the buyer. This negotiation strategy is typical of competitive negotiators that belongs to such emerging countries as China, Russia or Arab countries.

The non-zero-sum negotiation is the classical win-win situation, where both parties try to gain some reputation for further (trustful) business. This negotiation strategy is typical of cooperative negotiators that belongs to the most developed countries such as Sweden, Canada or Japan.

In terms of information, we also see both types. There are scenarios where all information is on the table and can be simply used to calculate the “best result”. But there are also scenarios, where not all information is visible to the other side, those can be hidden agendas or the information is plain false.

Expanding the pie #

It might help to cooperate to expand the pie, it is easier to get a big piece of the pie, if the pie itself is bigger. So understand if you are in a zero-sum game or if you can transition to a non-zero game. For this reevaluate the goal of the game. Is it it beat the other party, or to get something from a 3rd party? See Barry’s Armwrestling game.

Terminology #

BATNA your best alternative to a negotiated agreement

ZOPA stands for Zone of Possible Agreement

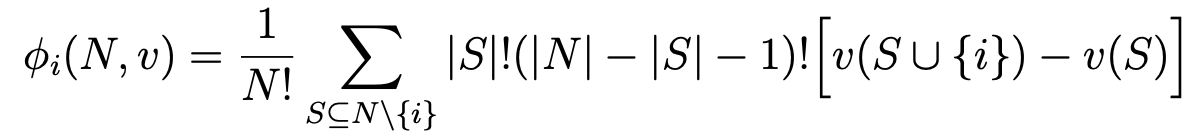

Shapley Value For each party in the group, it is the amount of pie created by that party joining others in the group,averaged across all possible orderings in which parties join the group.

Takeaways #

It is better to give than to receive. You would rather be the one making the offer since that person should get more than half of the pie. The advantage of being the one receiving the offer is you can guarantee yourself some money by saying yes to everything. –> The side with the smaller ε is more patient and gets the larger share.

Common Strategies #

In the world of Game Theory, those negotiation problems are coordination problems. Hence the goal is to coordinate and agree on an outcome both parties can live with.

There are multiple scenarios, where two or more parties try to claim a part of an underlying.

- sharing a taxi ride with different end-points

- splitting cloth

- debt collection

In addition to the different scenarios, there a are also possible ways to tackle them:

- proportional division

- sharing the pie

Basically there is no right nor false. You have to have a good feeling with the result. If you want to evaluate the outcome you need to first make sure that there is some kind of limit for you or your walkaway price.

As a seller, what is the least amount you’d be willing to accept before walking away? As a buyer, what’s the most you’d be willing to pay before before walking away? There are many names given to this number. In the classic book Getting To Yes, Roger Fisher and Bill Ury call this your BATNA, your best alternative to a negotiated agreement. Economists call this your reservation value.

Everything that is better than your reservation value will be a good outcome, probably not the best - but one, that does not give you a bad feeling. (See the winners curse on auctions)

The following strategies are not aimed to get the best result, but the one that could be titled as fair, hence we rate fairness over power.

two oranges #

sepearate

Proportional Division #

This applies to splitting an underlying in terms of the weight of each claims.

Splitting the Pie #

This is a method taught at Yale University by …

The pie is the difference between the benefit the negotiating parties could get if they work together and the sum of the benefits each party could get on its own.

The idea is it to first understand the claims and then to understand what the pie is to share. So first: What is the pie: What the two parties can create together vs. on their own.

The Talmud #

The 2,000 year old Babylonian Talmud forms the basis for Jewish civil, criminal and religious law. The text has a very interesting section on property law, we explore a bit deeper.

Two persons appearing before a court are holding a garment. If one says it’s all mine and the other says half of it is mine. Then the first will receive three-quarters and the latter one will receive one-quarter.

Proportional division would propose a two to one split, but the Talmud disagrees. Here is why:

Assuming we have 100 feet of cloth and one party claims all of the 100 feet, whereas the other party claim 50 feet. Under proportional division, the first party would get 2/3 of the cloth and the second party will get 1/3.

You could also argue, that the second party already conceded 50 feet to the first party by claiming (only) 50 feet. Hence the other 50 feet are in dispute. If we now divide this part equally (50:50), then the first party gets another 25 feet of cloth, making it 75 feet in sum. The second party gets then 25 feet. This approach then gives the Talmud 3/4 and 1/4 split.

Another example with slightly different numbers. First party claims 2/3 of the cloth and the second party still claims 1/2 of the cloth. This time, only (2/3 + 1/2) - 1 = 1/6 is in dispute. And therefore, as in the first example, the first party gets the conceded 1/2 + the half of the disputed 1/6, which is 1/12. This leaves the second party with the conceded 1/3 (as the first party only claims 2/3) + the half of the disputed 1/6.

This can become even more disturbing: property law in the Talmud

Offer and Counteroffer over time #

see also Game Theory: Ultimatum

Shapley Value #

Lloyd Shapley’s idea: members should receive payments or shares proportional to their marginal contributions. THe following three axioms need to hold:

- Interchangeable agents should receive the same shares/payments.

- Dummy players should receive nothing.

- If we can separate a game into two parts v=v1 +v2,then we should be able to decompose the payments

As Mark Twain famously said: Never try to teach a pig to sing. It wastes your time and annoys the pig.

I cut you choose #

Texas Shoot out #

Let’s look at the Texas Shoot-Out between Anju and Bharat with new numbers. Imagine Anju knows Bharat values the painting at $200, but Bharat only knows Anju’s value is somewhere between $800–$1,000.

If Bharat offered Anju a price of $400, would he expect Anju to say Buy or Sell?

- Buy

- Sell

That’s right. Anju values the painting at something between $800–$1,000. Buying at a price of $400 leaves her something between $400 and $600 ahead. In contrast, selling for $400 leaves her exactly $400 ahead. Thus buying always leaves Anju in a better position than selling when the price is $400.